In the classes that I teach I always have my students shape the front legs from square blanks to finished round, tapered cylinders entirely with hand tools — drawknife, spokeshave, and scraper. I even have them do a practice front leg before working on the two legs for their chair. All the hand work on the front legs is excellent practice for the more difficult rear legs which must be done with hand tools because of their bent shape. After shaping three front legs (one practice, and two for the chair) with hand tools, most students can shape the rear legs in about the same time as it took to shape the two front legs. There are many other ways, of course, to shape the front legs. The obvious, easiest, and fastest method is turning — the final shape of the leg is a tapered cylinder. And, if I want a faceted surface on the turned legs, the facets can be added afterwards with a spokeshave. Another way is to do most of the bulk stock removal on the bandsaw with a simple jig for knocking off the corners to form an octagonal blank, and then tapering one end with another bandsaw jig. This method gets you to a tapered octagonal blank very quickly but still leaves the hand work necessary to go from octagon to round. Although these methods can be faster, hand shaping is pleasant, dust free work, and can be done quickly with practice.

The process begins with the front leg blanks. The blanks should have the long grain as straight as possible. The grain orientation of the end grain does not matter — the finished legs will be tapered cylinders, so the leg can be rotated to the proper grain orientation at the time the rung mortises are drilled into the leg. I described in detail how to layout and mill the rough front leg blanks in this post. Below, left, is a rough front leg blank ready for final milling.

To final mill, I joint one face flat on the jointer. Next I joint an adjacent face square to the first face. You have a couple of options at this point. I simply set up my table saw for a 1-5/8″ rip cut and rip the blank twice, using the jointed faces as reference against the table and the fence. Another method is to rip the jointed blank slightly oversize on the bandsaw, again using the jointed faces as reference against the table and the fence. Then mill to final thickness, 1-5/8″ square, on the thickness planer. Once I have a milled blank, I trim to it to length — about 20″. This length is actually longer than is necessary and will be trimmed more than an inch after the front panel is assembled, so close to 20″ is fine. Below, right, is the leg blank milled to 1-5/8″ square and trimmed to 20″ long.

From here on out I will be using hand tools — drawknife, spokeshave, and scraper — to shape the blank into a finished leg. For instruction on how to use the drawknife and spokeshave I highly recommend the DVD by Brian, Drawknives, Spokeshaves and Travishers: A Chairmaker’s Toolkit, available here. There is also an excellent video on the Fine Woodworking web site where Brian demonstrates how to use a scraper. In almost all cases when using the drawknife and spokeshave, I hold the tool at a skewed angle relative to the path of the cut. I also use a slicing action, moving the tool side-to-side as I am making the cut. So, remind yourself when you are using these tools to skew and slice.

The first step in hand shaping the front leg is to knock off all four corners to form an octagonal blank. Shaping the octagon is by far the most important step in the hand shaping process. It is the only time you will really be able to see and compare each facet — there are only 8 facets, and they are relatively large — so it is easy to see if each facet matches the others. You can also see, just by looking at the edges of the facet, if there are dips or bumps. The octagon establishes the geometry of the shape. If you’ve made a good octagon, getting to a good cylinder is fairly easy since subsequent steps remove very little material. For this reason I spend a lot time making the octagon as perfect as possible.

I like to layout the octagon on both ends and along all four sides. The layout lines provide an excellent reference to work to. At some point, if you have a good eye and lots of experience you can cut an octagon without layout lines, but for beginners the layout lines really help. Chris Schwarz has an excellent blog post and video on laying out an octagon called Octagons Made Easy. In it he describes a no-measure method for laying out an equilateral octagon on the end of a blank. He uses a compass to mark the points of the octagon. I altered his method slightly by using a small square instead of the compass. Begin by drawing a diagonal line from one corner to the opposite corner. With the square against a corner move the blade until it just touches the diagonal line as shown on the left. Now place the square against each side and make a mark at the end of the blade as shown on the right.

Flip the square around and make another four marks, as shown on the left. Now simply connect the marks to form a perfect equilateral octagon. The beauty of this method is that it requires no measuring and will make a perfect octagon every time as long as the stock is square.

The next step is to extend the points of the octagon down the length of the blank on all four sides. I used to reset the square so that it extended from the edge of the blank to the edge of a facet — about 15-32″. I was demonstrating this in class one day, and my student, David Blois, had a brilliant idea — simply leave the square set (with the blade extending as far as the diagonal line) and layout the edges of the facets from the opposite edge of the blank. I love the simplicity of this process. In it’s most basic form, if you need to draw an octagon down the length of square stock, draw a diagonal on one end, set the blade of the square to the diagonal, and use the square to layout the facets of the octagon. Below I am drawing one layout line using the top edge as a reference. And below that, I am drawing the second layout line from the bottom edge. Repeat this for all four sides of the blank.

As I mentioned, shaping the octagon is the most important step in hand shaping the leg. Do a good job here and the subsequent steps are fairly easy. I use a methodical process for shaping each facet, but it is difficult to show the subtleties in a photograph so the illustrations highlight what may be difficult to see in the photos. Begin, as described above, by laying out the facets of the octagon on both ends of the blank, and along it’s length on all four sides.

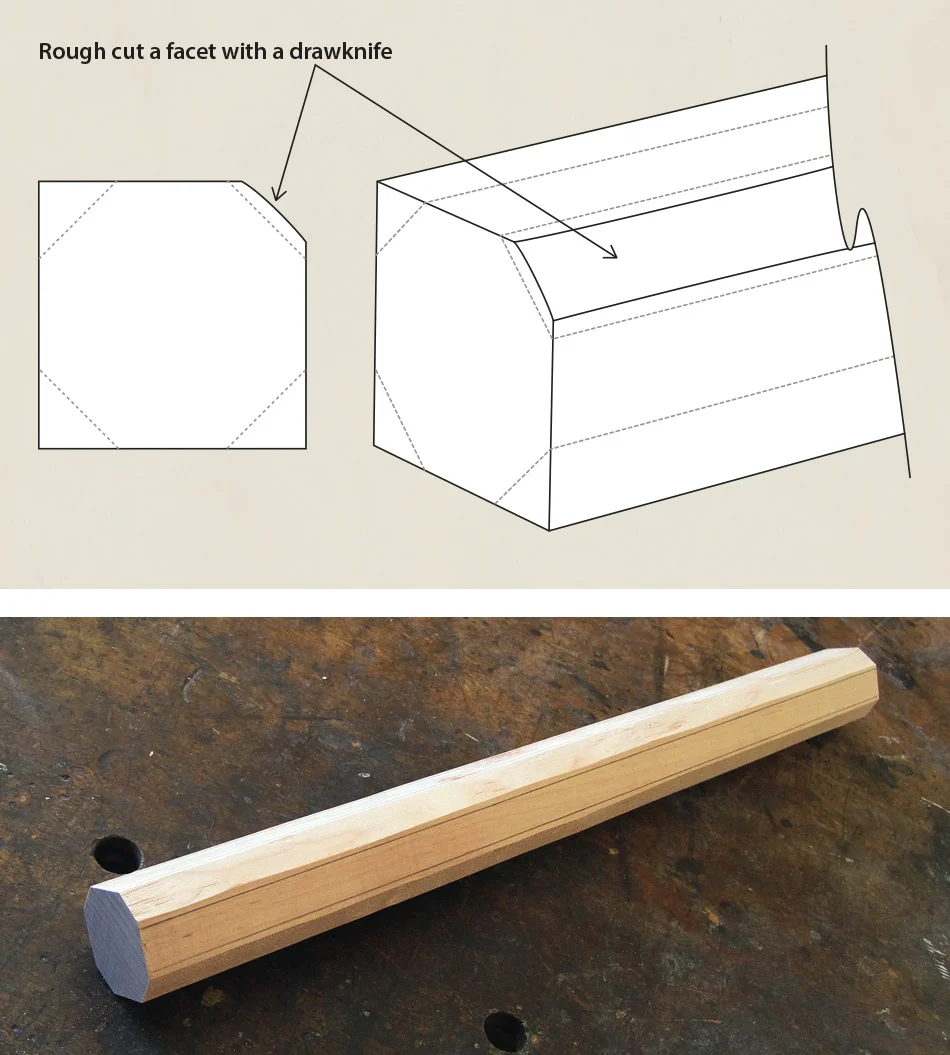

Next knock off most of a corner of a facet with the drawknife getting as close to the layout line as you are comfortable with.

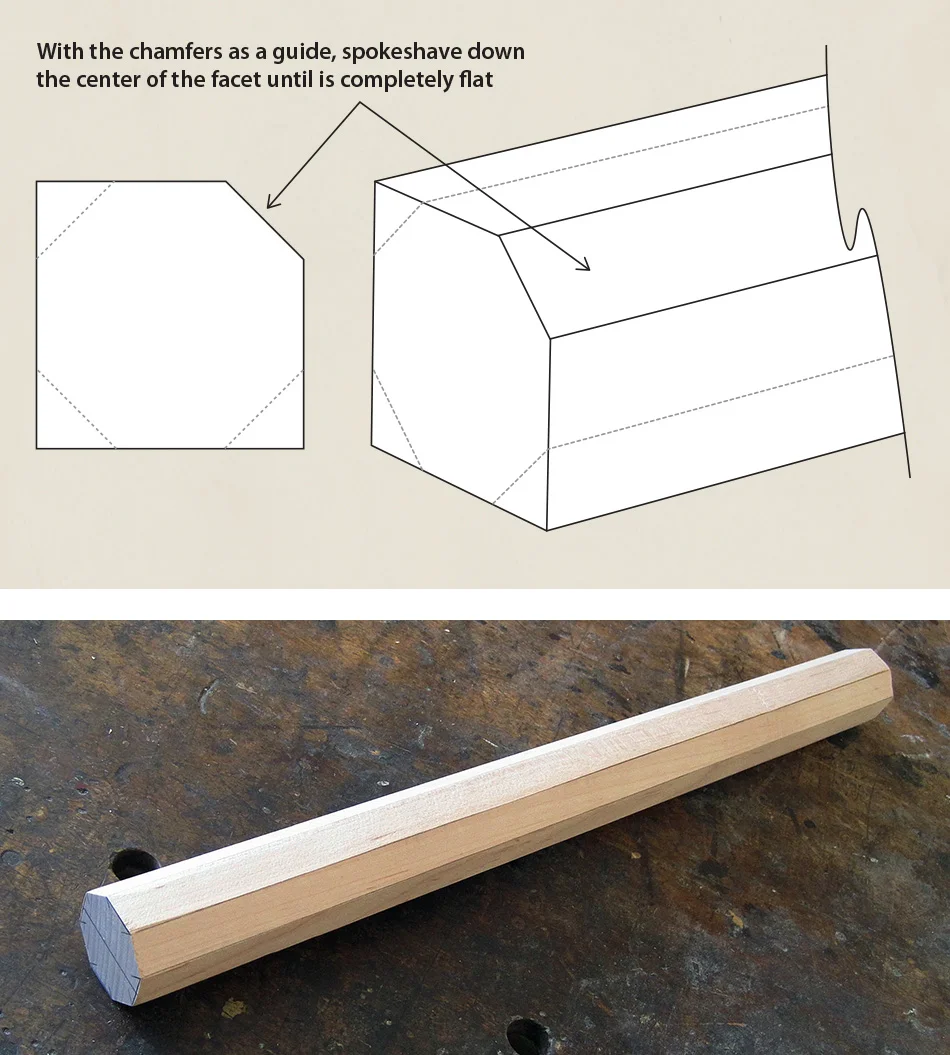

Switch to a flat bottomed spokeshave and cut shallow chamfers up to both layout lines. It’s much easier to cut to the line when making these narrow chamfer cuts as opposed to making full width cuts. The chamfers define the limit of the facet and become a reference for making the final flat facet.

Now start making cuts down the center of the facet with the spokeshave. As you do, the shavings will get wider and wider until you reach the full width of the facet as defined by the chamfers and the layout lines. I get as close to the layout lines as I can without cutting into them. The object is to make a straight, flat facet end-to-end as well as side-to-side. The tendency is to have the facet crown side-to-side, but a flat facet works better.

The next step is to layout the taper. The leg tapers from 1-5/8″ at it’s full diameter to 1″ at the bottom. Set a square to 5/16″ and mark two opposite sides as shown on the left. Measure between the two marks to confirm that the distance between them is 1″. If not, adjust the square until it is. Then mark a 1″ octagon all the way around the blank as shown on the right.

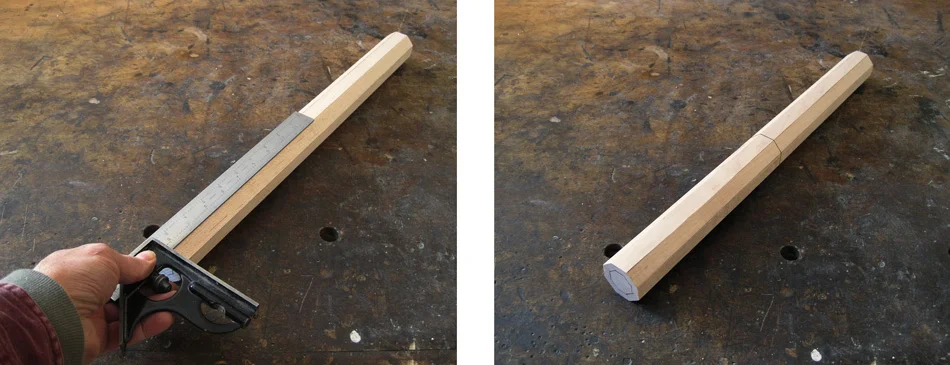

The taper starts 9-1/2″ from the bottom. Use a square set to 9-1/2″ to mark the beginning of the taper on all eight facets.

Begin shaping one facet of the taper. Use a drawknife to remove the bulk of the material. Start by taking short cuts starting about two or three inches from the bottom. Make each additional cut a little longer until you get close to the mark at 9-1/2″. Now switch to the spokeshave. Before making any cuts with the spokeshave I like to check the flatness of the taper with a straight edge. The blade from the combination square works great for this. If there are bumps or hollows first concentrate on removing those. Then make long cuts with the spokeshave until you have a flat taper extending from the mark at 9-1/2″ all the way to the bottom of the leg. Be careful not to cut too far beyond the 9-1/2″ mark — the rung mortises begin a little bit above this mark and you’ll need a full diameter cylinder. Here is the leg with one tapered facet cut.

You can also evaluate the flatness of the taper cut visually. A flat facet will have straight edges from the beginning of the taper to the bottom as shown on the left. A concave edge indicates a bump as shown in the center. And a convex edge indicates a hollow as shown on the right. As you get more experienced and train your eye you can rely on these visual clues to determine if the facet is flat.

Next taper the opposite side from the first taper cut.

Then rotate the leg 90° and make the third taper cut. And rotate again, this time 180°, and make the fourth taper cut.

Finally, taper the four remaining facets. Begin by removing the bulk of each facet with a drawknife. Then finish the taper with the spokeshave. Here is the finished tapered leg at the octagon stage. It may seem like a lot of work to get the leg to this stage but the work you do getting the octagon as perfect as possible will pay off in the next steps. At this point the geometry of the shape is set and from here on out you will only be making small cuts, so it is relatively easy to maintain the geometry and end up with a true tapered cylinder.

The next step involves taking the leg from 8 sides to 16 sides by shaving each corner into a facet. Since the facets are so much smaller, the problem most people have is seeing them and keeping them equal in size. I had a student last year who was shaping the back of a walnut rear leg from 8 to 16 sides and he was having a lot of trouble just seeing the facets, especially in the dark walnut. We solved the problem by drawing reference lines around the leg as shown here.

As he shaved an edge he left a gap in the pencil line on the facets he shaved and dashes on the remaining facets. When the dashes and gaps are equal he had a consistent 16-sided leg similar to the front leg shown here. This really helped him see the facets, keep them straight end-to-end and consistent in width.

After 16 sides, the next step is to shape the leg to 32 sides. Although it’s not absolutely necessary it can help to renew the reference lines around the leg as shown here.

At this point I am removing very little material and I actually count the number of strokes I take on each facet as well as keep an eye on the dashes and gaps in the pencil line to make sure the facets are consistent. Here is the leg shaped to 32 sides.

The next step is to go to a fully round cylinder. I simply go around the leg knocking off facets with the spokeshave. Once I’ve gone all the way around I use my hand to feel for bumps and flats. I knock off bumps with the spokeshave and fix flats by shaving on either side of the flat. I stop when I’m satisfied that I have a consistent, fully round, tapered cylinder as shown here.

The final shaping is done with the card scraper. At this point the leg will have very small facets and may have tear-out as well. You can see the tear-out left by spokeshave in this photo.

I hold the scraper as close to vertical as I can and still get a shaving, skew it relative to the direction of the cut, and take light cuts to remove the remaining facets. When I work the areas with tear-out I make sure to take strokes coming from different directions so that I don’t dig a hole or make a flat as I work.

Here is the same leg with the tear-out removed. With a leg in this shape I can go directly to 220 grit sandpaper.

This may seem like a lot of work, but the methodical, step-by-step process yields beautiful, consistent results. And using this method works particularly well on the rear legs. Once you get some practice with this technique the individual steps go very quickly. It is pleasant and satisfying work.

Although I have demonstrated how to shape the legs to full round, there is no reason, if you prefer, to stop shaping at 16 or 32 facets. This leaves a nice texture on the legs that is a pleasure to touch while sitting in the chair. For example, when Brian shapes the parts for the Greenwood chair he stops after 16 sides.

In the next post I’ll move onto to shaping the rear legs — my favorite part of making this chair.

Side Chair Build Series Links:

- Next Post: Hand Shaping, Part 3 — Rear Legs

- Previous Post: Hand Shaping, Part 1 — Tools